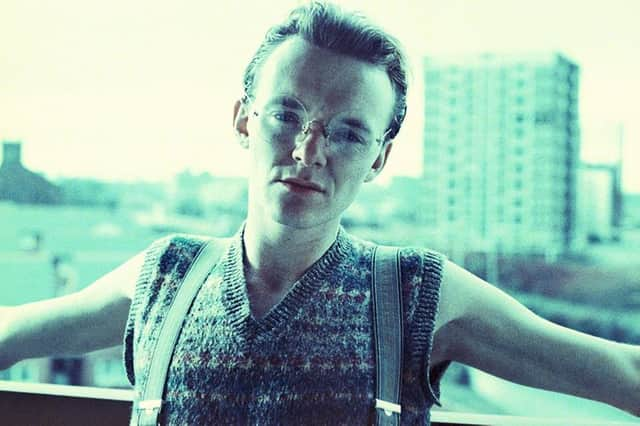

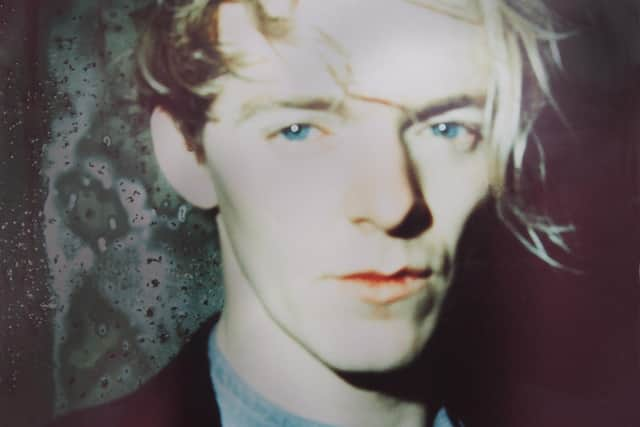

Micky Greaney: 'People don’t see how easy things are if you set your mind to something'

But such has been the warmth of the reaction to the release of the album And Now It’s All This, it looks set to open a whole new chapter for the now 57-year-old Birmingham singer-songwriter.

“Yeah, they have done great,” he says, praising the efforts of John Purcell and Chris Coleman of indie label Seventeen Records in rescuing 13 tracks that he recorded with seasoned producers John Leckie and John Cornfield in the mid-1990s and transforming them, with the mastering skills of John A Rivers, into a finished album.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The chances of it happening looked kind of remote a couple of years ago, and now it’s happening. It’s amazing,” he says.

Back in December 1995 when Greaney and his band had embarked on the first set of sessions at Abbey Road studios in London with Leckie, a veteran producer and engineer who had also worked with the likes of Paul McCartney, Pink Floyd, Simple Minds, the Stone Roses and Radiohead, things had looked optimistic.

The previous year the singer-songwriter had released his debut album Little Symphonies For The Kids. Produced by Bob Lamb (UB40, Duran Duran) and featuring members of Ocean Colour Scene, it had prompted interest in him from music mogul Safta Jaffrey, and major label Parlophone. On its back, Greaney had assembled a 12-piece band who had performed at Ronnie Scott’s club in Birmingham – a setting which, he says, “was perfect for us to do...it wasn’t like a pub, people dressed up to go there and everyone sat down and paid attention”.

Greaney recalls that a “a lot of the lads (in the band) had got quite excited about” being in the hallowed surroundings of Abbey Road, but he was focused on the task in hand. “You’re at Abbey Road with John Leckie, it’s probably not going to happen all that often in your life, so there was a bit of tourism going on in a way, a few people looking around and taking photos; I was literally there to work,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the songs already fully written and arranged, Leckie sought to record Greaney and the band live. “He sets up all the mics and he goes ‘go’ and ‘stop’, basically that’s all he says, apart from ‘OK’ at the end and ‘Shall we do that again?’ I quite liked that,” Greaney says. “There were some long songs in my set so to have people play a very long song all at the same time and you couldn’t make any mistakes, it was quite interesting. He was like one of those proper old boxing trainers or something like that. If you can’t actually just lay it down he’s not interested. You’ve got to be able to play it.”

The recordings featured the Enigma String Quartet – Caroline Bodimead, Charley Beresford, Ellen Brookes and Liz Tollington, four students who Greaney had found at the Birmingham Conservatoire.

“There were 13 of us that went to Abbey Road, but in order to get there I had to sack a hell of a lot of people, and then hire other people who were not quite there but were on my list – that’s where the Enigma Quartet were, really,” he says. “When I first met them they were first years but they were off working with third-year students. Then by the time things were getting going they were at absolutely the right page, they were perfect. They’d matured a little bit as players…

“I really liked the girls, they just had a certain charm about them, so they were always going to be the actual quartet (on the record), and then they’ve gone on and done great stuff on their own.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe second set of sessions were done with John Cornfield at Sawmills Studio in Cornwall in April 1996. Despite its idyllic setting by the River Fowey, Greaney says he “didn’t take to” the residential studio during his brief stay. “First of all it was like a rescue mission, it was just me and John Cornfield at first, and in two days you can’t really mix anything. John Leckie, having given me a crash course in being a sound engineer at Abbey Road, showed me it was really simple – all the channels do the same thing. So me and John Cornfield tried to make some sense of what we’d done at Abbey Road, and then we were able to get the band down and record a few more songs.”

Sadly, a deal to release the album failed to materialise and for more than 25 years the mastertapes of Greaney’s recordings are thought to have languished in the office of Safta Jaffrey. The singer had not forgotten them, though. He recalls that years later, when he was working with Bauhaus bassist-turned-producer David Jay and an orchestra in Prague, Leckie had been “really cross” with him for trying to do another version of Sweetheart, which they’d originally recorded at Abbey Road.

“I’d sent it to him and he was like, ‘What are you doing? You’ve already done it.’ I think that prompted him to send me slightly different mixes that he had and he sent them to John Rivers at Woodbine.”

That set the ball rolling on completing And Now It’s All This – named after a quote from John Lennon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore embarking on a solo career, Greaney had been in two Birmingham bands, The French Way and The Girls. “The Girls was a proper collaboration – me and Slim (Cartwright), the singer out of The Rag Dolls and (me) the singer out of The French Way. We were always a lot underneath The Rag Dolls, really, they were massive compared to us, so then for me and Slim to get together and start singing together that was a real step up for me, that was a real graduation, a learning process.

“At that time Slim had way better songs than me and was way more accomplished. If they did a gig it was packed, if we did a gig there was no one there. So for Slim, that was big undertaking. I thought, I like his songs, I’ll be in a band with him – and also we played football together, so that helped.”

The pair had come into contact as rival buskers around Birmingham city centre. In the 1980s Cartwright would busk in a trio with Dave Kusworth and Andy Wickett, the former frontman of the nascent Duran Duran, while Greaney performed alone. “I was always that bit younger than everyone else, and they’d be looking in their guitar case (for tips from onlookers) and go, ‘we’re a bit shy, we’re not earning as much’ and they’d hear this noise across the way and instead of the Rolling Stones (which the trio would play), there’d be Bob Marley and other stuff going on and they’d be like, ‘who’s this stealing our money?’ That’s really how I first came into their context.”

Greaney would go on to be a significant figure in the city’s music scene, running the Catastrophe Club at the Lamp Tavern in Digbeth at the turn of the 1990s. “I went to Dublin a lot when I was younger, it just had a great vibe. You’d have people like Martin Scorsese sitting down talking to Declan MacManus (Elvis Costello) in a pub and the enrgy of the place was off the charts. It was just about to be the (European) City of Culture and I’d auditioned for The Commitments and there was this great little theatre scene, kind of improv stuff...and I thought I’d really like to do that but like a gig but not a gig at all. So it was always pretty silly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We’d have a John Lennon spectactular where everyone had to play John Lennon songs or a Halloween special with everyone dunking apples and Trish (Keenan) from Broadcast would be there and stuff like that.

“The other thing about the Lamp Tavern was there were curtains so it was like a tiny theatre and Slim would sing Five Years (behind the curtains) and I’d go, if you close your eyes it’s just like David Bowie singing and I’d go (to the audience) Shhh’ and he’d finish singing and there’d be no applause. It was just fun, it was silly. We’d finish off busking and then we’d do that.”

Little Symphonies For the Kids, the album that Greaney cut with Bob Lamb in 1994, is another lost gem. Looking back, the singer says his prime motivation at the time was to win back the affection of his then girlfriend. “I thought, ‘I’d better show you that I can do something other than being completely insane’, so I thought ‘I’ll make Little Symphonies, that would be good’. There was this lovely club on Broad Street and I thought, ‘I’ll put a band in there and you’ll love me again, it’s going to work, it’s going to be brilliant’ – and ultimately it kind of did.”

In the wake of the release of And Now It’s All This, Greaney is raising his sights again. He talks of putting on two gigs in home city and says he would like to go back out to Prague. “The fun part about it was meeting David (Jay) and Marc Warren, who’s an actor who plays Van Der Valk (in the ITV detective series). I played a gig and then Pat Fish (aka The Jazz Butcher) played and David Jay headlined and then we all got up together.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe and Warren have stayed in touch. “I think good art is when two artists can go and have a real old chat and love each other a little bit more after it,” Greaney says. “Me and Marc text (each other) pretty much every day, which is really nice… It’s always really stupid and just good fun.

“I like meeting people, it’s better doing stuff,” he adds. “That’s why I did the Catastrophe Club, that’s why I did Abbey Road, that’s why I had a big band. All these people, they had a beautiful time in their lives and they went to Abbey Road. People don’t see how easy things are if you set your mind to something.”

And Now It’s All This is out on Seventeen Records now. https://mickygreaney.bandcamp.com/